This is a rewrite/repost of an older blog post of mine. The code is available on GitHub.

TL;DR: Started with a WASM Blake3 that I wanted to improve. Wrote a naive JS port (~2000x slower), then optimized it step by step—profiling, inlining, avoiding allocations, using local variables instead of arrays, and exploiting little-endian. Pure JS ended up 1.6x faster than WASM. Then I generated SIMD WASM at runtime (no .wasm file shipped) for a final result of 2.21x faster than the original.

Blake3: A JavaScript Optimization Case Study

Blake3 is a popular hashing algorithm that performs a few times faster than others like SHA-256. A couple of months ago I needed to use it in a browser and was a bit disappointed with the throughput and the size of the WASM module, so here's how I made it faster.

It achieves this by:

- Using fewer rounds in its compression function (see Too Much Crypto for the rationale), and

- Enabling high parallelization where each chunk of data can be processed in parallel before the merge, through the Merkle Tree-style splitting of the data and merging of the two nodes to form parents.

This article will focus on the technical details of how I made Blake3 run faster in browsers.

However, since Blake3 is not part of the SubtleCrypto API, native implementations of the algorithm are not provided in the browser. This leaves developers to have to use other implementations. However, currently, there is only a WASM implementation.

Yet the WASM implementation does not use SIMD which seems to be wasted potential, so in this blog, I want to explore the performance of a pure JavaScript implementation of the algorithm and then do some black magic to use SIMD.

The Problem With WASM

High shipping cost. This comes in two forms. First of all, WASM files are relatively large for what they do. The simple Blake3 implementation produces a 17KB binary file that can not be compressed any further, while a JS file could be. Gzipping a WASM file does not have any effect for obvious reasons.

The second issue—and this is more from a tooling aspect—is that the maintenance cost of a JS library that uses WASM could be a bit harder than it should be. You have to consider different runtimes and how you want to get the WASM file. And personally as a developer, I'd rather not depend on a process that involves loading a WASM file.

JavaScript is simple: you can ship one file and it will just work. You don't even have to care about much. And of course, these points I'm making are coming from a point of preference.

However, eventually in this blog I will use WebAssembly, but at no point do I intend to ship a .wasm file. So let's go.

Setting Up The Benchmark

We can't improve what we can't measure, and yet there are different JS runtimes around. To keep the data simpler to understand, I primarily focus on the JS performance on V8. Maybe in the future I can go through the same process in some other engines and that could be an interesting article of its own.

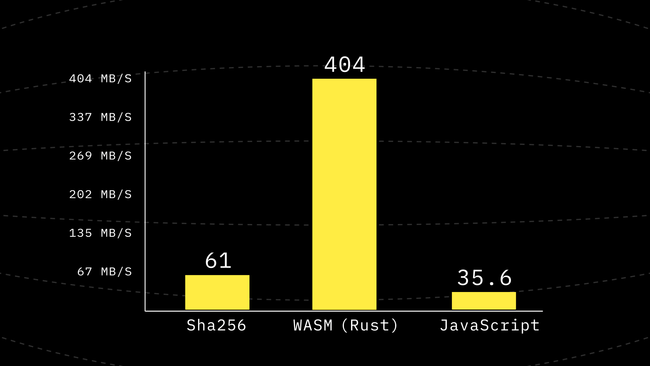

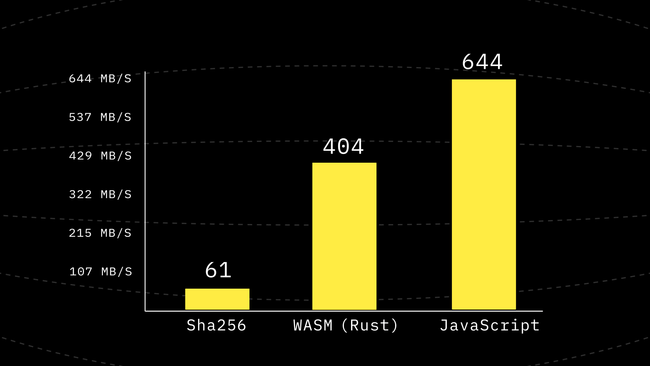

The benchmark is simple: I generate some 1MB random data and use Deno.bench to compare the performance of the different hash functions on some standard data sizes. I'm going to run these on an Apple M1 Max and compare the results.

To get started I can set a baseline by comparing an implementation of SHA-256 and a WASM compilation of the hash function from the official Rust implementation.

import { hash as rustWasmHash } from "./blake3-wasm/pkg/blake3_wasm.js";

import { sha256 } from "https://denopkg.com/chiefbiiko/sha256@v1.0.0/mod.ts";

// Share the same input buffer across benchmarks.

const INPUT_BUFFER = new Uint8Array(1024 * 1024);

const BENCH_CASES = (<[string, number][]>[

["96B", 96],

["512B", 512],

["1Kib", 1 * 1024],

["32Kib", 32 * 1024],

["64Kib", 64 * 1024],

["256Kib", 256 * 1024],

["1MB", 1024 * 1024],

]).map(([humanSize, length]) => {

// Slice up to `length` many bytes from the shared array.

const array = new Uint8Array(INPUT_BUFFER.buffer, 0, length);

return <[string, Uint8Array]>[humanSize, array];

});

// Randomize the input.

for (let i = 0; i < INPUT_BUFFER.length; ) {

let rng = Math.random() * Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER;

for (let j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

INPUT_BUFFER[i++] = rng & 0xff;

rng >>= 8;

}

}

function bench(name: string, fn: (array: Uint8Array) => any) {

for (const [group, input] of BENCH_CASES) {

Deno.bench({

name: `${name} ${group}`,

group,

fn() {

fn(input);

},

});

}

}

bench("Sha256", sha256);

bench("Rust (wasm)", rustWasmHash);📌 You can also see this initial state of the repo at this point of the journey on the GitHub link. As I make progress in the blog there will be new commits on that repo. So in case you want to jump ahead and just look at the outcome, you can just go to the main branch on that repo and check it out!

My First Pure JS Implementation

For the first implementation, I can skip over any creativity. My goal is to be more concerned with the correctness of the algorithm so I mainly base the initial implementation on the reference_impl.rs file from the official Blake3 repository. The only adjustment is that I only care about implementing a hash function and not an incremental hasher.

As my main entry point, I have the hash function defined as:

export function hash(input: Uint8Array): Uint8Array {...}In this function, I mainly split the input into full chunks (that is 1024 bytes), and run the compression function on each 16 blocks that make up the chunk. (So each block is 64 bytes.)

At the end of compressing each chunk of data I push it to the chaining value stack, and after that—depending on where I am in the input—I merge a few items on the stack to form the parents. This is done by counting the number of 0s at the end of the chunk counter (number of trailing zeros) when written in binary. And in case you're wondering why that would work, I want you to notice how that number is the same as the number of parents you can walk up the tree while still being the right child repeatedly.

The rest of the code is mostly the implementation of the compress function that has one job:

- Take one block of input (64 bytes or 16 words) and 8 words called

cv, and compress it down to 8 new words. These 8 words are also called the chaining value. - To hash each chunk of data (1024 bytes, 16 blocks) I repeatedly call the compress function with each block and the previous

cv. However, for the first block in each chunk since there's no previous chaining value, I default the first one toIVwhich stands for Initialization Vector.

🤓 Fun Fact: Blake3 uses the same IV values as SHA-256—the first 32 bits of the fractional parts of the square roots of the first 8 primes 2..19. It also uses the round function from ChaCha, which itself is based on Salsa.

Setting Up The Test Ground

To make sure I'm doing things correctly, I use a rather large test vector that is generated using the Rust official implementation and test my JS implementation against it. This way on each iteration and change I make I can make sure I'm still correct before getting hyped about performance. A no-op hash function is always the fastest hash function, but I don't want that, do I?

First Look At The JavaScript Performance

At this point, my first JavaScript port is about ~2000x slower than WebAssembly. Yet looking at the code it is expected—after all, the first iteration is about keeping it as close as possible to an academic reference implementation. And that comes with a cost.

Step 1: Using a Profiler

See this commit on GitHub: add readLittleEndianWordsFull

Although the initial code is really bad, it is not surprising and I can clearly see way too many improvements I could make. But to set a better baseline it's better if my first improvement is something that can benefit me the most with the least amount of change to the code.

We can always use a profiler to do this. V8 is shipped with a really nice built-in profiler that is accessible through both Deno and Node.js. However, at the point of writing this blog, only Node comes with the pre-processing tool that takes a V8 log and turns it into a more consumable JSON format.

First, we need a simple JS file that could use the hash function we want to profile:

// prof.ts

import { hash } from "../js/v0.ts";

const INPUT_BUFFER = new Uint8Array(256 * 1024);

for (let i = 0; i < INPUT_BUFFER.length; ) {

let rng = Math.random() * Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER;

for (let j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

INPUT_BUFFER[i++] = rng & 0xff;

rng >>= 8;

}

}

for (let i = 0; i < 20; ++i) {

hash(INPUT_BUFFER);

}We can run the following commands to get the profiling result:

deno bundle prof.ts > prof.js

node --prof --prof-sampling-interval=10 prof.js

node --prof-process --preprocess *-v8.log > prof.jsonLooking at the result of the profiler we can see that readLittleEndianWords is one of the hottest functions in the code. So let's improve that as our first step.

Looking at the source of readLittleEndianWords we can see that there are a few conditionals that could have been left out if we knew that we are reading a full block of data. And interestingly enough at every part of the code, we always know that we are reading a full block except for the very last block of data. So let's implement a new variant of the function that leverages that assumption:

function readLittleEndianWordsFull(

array: ArrayLike<number>,

offset: number,

words: Uint32Array,

) {

for (let i = 0; i < words.length; ++i, offset += 4) {

words[i] =

array[offset] |

(array[offset + 1] << 8) |

(array[offset + 2] << 16) |

(array[offset + 3] << 24);

}

}This function is a lot more straightforward and should be relatively easier for a good compiler to optimize.

For how small of a change I made, this is definitely a great win. But I'm still far away from the WebAssembly performance.

Step 2: Precomputing Permute

See this commit on GitHub: Inline Permutations

For this step, I want to draw your attention to these particular lines of the code:

const MSG_PERMUTATION = [2, 6, 3, 10, 7, 0, 4, 13, 1, 11, 12, 5, 9, 14, 15, 8];

// ...

function round(state: W16, m: W16) {

// Mix the columns.

g(state, 0, 4, 8, 12, m[0], m[1]);

g(state, 1, 5, 9, 13, m[2], m[3]);

// ...

}

function permute(m: W16) {

const copy = new Uint32Array(m);

for (let i = 0; i < 16; ++i) {

m[i] = copy[MSG_PERMUTATION[i]];

}

}

function compress(...): W16 {

// ...

const block = new Uint32Array(block_words) as W16;

round(state, block); // round 1

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 2

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 3

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 4

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 5

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 6

permute(block);

round(state, block); // round 7

permute(block);

// ...

}Looking at the code above we can see some annoying things. On the top of the list are the two new Uint32Array calls we have, which are unnecessary allocations and moves of bytes that could be avoided. The other thing that we can notice is that all 6 permute calls are deterministic, and this opens the possibility of pre-computing a look-up table.

In order to inline permute we could change round so we could tell it about an access order it should use rather than actually moving the bytes:

function round(state: W16, m: W16, p: number[]) {

// Mix the columns.

g(state, 0, 4, 8, 12, m[p[0]], m[p[1]]);

g(state, 1, 5, 9, 13, m[p[2]], m[p[3]]);

// ...

}Let's write code that generates this for us:

const MSG_PERMUTATION = [2, 6, 3, 10, 7, 0, 4, 13, 1, 11, 12, 5, 9, 14, 15, 8];

// 0, ..., 15

let numbers = MSG_PERMUTATION.map((_, idx) => idx);

for (let i = 0; i < 7; ++i) {

console.log(`round(state, m, [${numbers.join(",")}]);`);

numbers = MSG_PERMUTATION.map((p) => numbers[p]);

}Running the code above produces:

round(state, m, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]);

round(state, m, [2, 6, 3, 10, 7, 0, 4, 13, 1, 11, 12, 5, 9, 14, 15, 8]);

round(state, m, [3, 4, 10, 12, 13, 2, 7, 14, 6, 5, 9, 0, 11, 15, 8, 1]);

round(state, m, [10, 7, 12, 9, 14, 3, 13, 15, 4, 0, 11, 2, 5, 8, 1, 6]);

round(state, m, [12, 13, 9, 11, 15, 10, 14, 8, 7, 2, 5, 3, 0, 1, 6, 4]);

round(state, m, [9, 14, 11, 5, 8, 12, 15, 1, 13, 3, 0, 10, 2, 6, 4, 7]);

round(state, m, [11, 15, 5, 0, 1, 9, 8, 6, 14, 10, 2, 12, 3, 4, 7, 13]);Using the above-generated code inside compress we get another 1.6x improvement—it's not as huge a boost as we had, but it's in the right direction.

Step 3: Inlining Round Into Compress

See this commit on GitHub: Inline Round into Compress

Continuing to focus on the previous area, we can also see that there is no strong need for round to be its own function. If we could just do the same job in compress, we could maybe use a for loop for the 7 rounds we have. And hopefully not having to jump to another function could help us.

To achieve that we first modify g to take the block directly and make it up to g to read from the array of block words:

function g(state: W16, m: W16, x: number, y: number, a, b, c, d) {

const PERMUTATIONS = [

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 2, 6, 3, 10, 7, 0, 4,

13, 1, 11, 12, 5, 9, 14, 15, 8, 3, 4, 10, 12, 13, 2, 7, 14, 6, 5, 9, 0, 11,

15, 8, 1, 10, 7, 12, 9, 14, 3, 13, 15, 4, 0, 11, 2, 5, 8, 1, 6, 12, 13, 9,

11, 15, 10, 14, 8, 7, 2, 5, 3, 0, 1, 6, 4, 9, 14, 11, 5, 8, 12, 15, 1, 13,

3, 0, 10, 2, 6, 4, 7, 11, 15, 5, 0, 1, 9, 8, 6, 14, 10, 2, 12, 3, 4, 7, 13,

];

const mx = m[PERMUTATIONS[x]];

const my = m[PERMUTATIONS[y]];

// ...

}Using this pattern allows us to modify compress's calls to round into:

let p = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 7; ++i) {

// Mix the columns.

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 0, 4, 8, 12);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 1, 5, 9, 13);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 2, 6, 10, 14);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 3, 7, 11, 15);

// Mix the diagonals.

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 0, 5, 10, 15);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 1, 6, 11, 12);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 2, 7, 8, 13);

g(state, block_words, p++, p++, 3, 4, 9, 14);

}This change removes one depth from a call to compress to the deepest function it calls, and surprisingly it is another 1.24x improvement in the performance, making it a 1.98x improvement including the previous step. Which means just by inlining the function a little and precomputing the permutations we have almost doubled the performance.

Step 4: Avoid Repeated Reads and Writes From the TypedArray

See this commit on GitHub: Use Variables Instead of an Array For State

A Uint32Array is fast, but constantly reading from it and writing to it might not be the best move, especially if we have a lot of writes. A call to g performs 8 writes and 18 reads. Compress has 7 rounds and each round has 8 calls to g, making up a total of 448 writes and 1008 reads for each 64 bytes of the input. That's 7W, 16R per input byte on average (not considering the internal nodes in the tree). This is a lot of array access.

So what if state was not a Uint32Array and instead we could use 16 SMI variables? The challenge here is that g depends on dynamic access to the state, so we would have to hardcode and inline every call to g in order to pull this off.

This is another case where meta-programming makes the code easier to generate:

const w = console.log;

function right_rot(x, y, r) {

w(` s_${x} ^= s_${y};`);

w(` s_${x} = (s_${x} >>> ${r}) | (s_${x} << ${32 - r});`);

}

function g_inner(a, b, c, d, d_rot, b_rot) {

w(` s_${a} = (((s_${a} + s_${b}) | 0) + m[PERMUTATIONS[p++]]) | 0;`);

right_rot(d, a, d_rot);

w(` s_${c} = (s_${c} + s_${d}) | 0;`);

right_rot(b, c, b_rot);

}

function g(a, b, c, d) {

g_inner(a, b, c, d, 16, 12);

g_inner(a, b, c, d, 8, 7);

}

for (let i = 0; i < 8; ++i) {

w(`let s_${i} = cv[${i}] | 0;`);

}

w(`let s_8 = 0x6A09E667;`);

w(`let s_9 = 0xBB67AE85;`);

w(`let s_10 = 0x3C6EF372;`);

w(`let s_11 = 0xA54FF53A;`);

w(`let s_12 = counter | 0;`);

w(`let s_13 = (counter / 0x100000000) | 0;`);

w(`let s_14 = blockLen | 0;`);

w(`let s_15 = flags | 0;`);

w(``);

w(`for (let i = 0; i < 7; ++i) {`);

// Mix the columns.

g(0, 4, 8, 12);

g(1, 5, 9, 13);

g(2, 6, 10, 14);

g(3, 7, 11, 15);

// Mix the diagonals.

g(0, 5, 10, 15);

g(1, 6, 11, 12);

g(2, 7, 8, 13);

g(3, 4, 9, 14);

w(`}`);

w(`return new Uint32Array([`);

for (let i = 0; i < 8; ++i) {

w(` s_${i} ^ s_${i + 8},`);

}

for (let i = 0; i < 8; ++i) {

w(` s_${i + 8} ^ cv[${i}],`);

}

w(`]);`);Something about meta-programming that has always fascinated me is how the generator code does not always have to be beautiful or future-proof. It just needs to do its job in the stupidest but simplest possible way.

Running the code above generates a monstrosity (you can check it out on the GitHub repository), but here's the general idea:

let s_0 = cv[0] | 0;

// ...

let s_7 = cv[7] | 0;

let s_8 = 0x6a09e667;

let s_9 = 0xbb67ae85;

let s_10 = 0x3c6ef372;

let s_11 = 0xa54ff53a;

let s_12 = counter | 0;

let s_13 = (counter / 0x100000000) | 0;

let s_14 = blockLen | 0;

let s_15 = flags | 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 7; ++i) {

s_0 = (((s_0 + s_4) | 0) + m[PERMUTATIONS[p++]]) | 0;

s_12 ^= s_0;

s_12 = (s_12 >>> 16) | (s_12 << 16);

s_8 = (s_8 + s_12) | 0;

s_4 ^= s_8;

s_4 = (s_4 >>> 12) | (s_4 << 20);

// ... 90 more lines of these

}

return new Uint32Array([

s_0 ^ s_8,

// ...

s_7 ^ s_15,

s_8 ^ cv[0],

// ...

s_15 ^ cv[7],

]) as W16;And that's how we get another 2.2x performance boost. We're now almost in the same order of magnitude as the WASM implementation.

Step 5: Avoid Copies

See this commit on GitHub: Avoid Copies

We have already seen the impact not copying data around into temporary places can have on performance. So in this step, our goal is simple: instead of giving data to compress and getting data back, what if we could use pointers and have an in-place implementation of compress?

Of course, there are no pointers in JavaScript, but not having to construct new instances of UintNArray is good enough for us. We could always pass an offset along a Uint32Array as a number to determine the starting range. Since compress already knows the size of all of the inputs it has to take, we would not need a closing range.

With that being said, here is the new signature for compress:

function compress(

cv: Uint32Array,

cvOffset: number,

blockWords: Uint32Array,

blockWordsOffset: number,

out: Uint32Array,

outOffset: number,

truncateOutput: boolean,

counter: number,

blockLen: Word,

flags: Word,

) {}If you pay attention closely you can see that along with the new out buffer, we also have added a new boolean flag called truncateOutput. This comes from the observation that in our current use case of the compress function we only ever need 8 words of the output. However, compress is capable of generating 16 words of output that are used in the XMD mode of the hash function (when we want larger than the default 256-bit output). The current hash function does not provide this functionality but we can still keep the possibility and future-proof the function.

The main part here is that now instead of returning a W8 (which used to be a new Uint32Array every time), we can simply ask the caller where the output has to be written to.

Another huge part of this change is around not using an array for the cvStack since we can benefit from having two items in the stack right next to each other in the same Uint32Array.

Using a Uint32Array for the stack:

// Old

const cvStack: W8[] = [];

// New

const cvStack = new Uint32Array(maxCvDepth << 3);

let cvStackPos = 0;Now with this new approach, pushing to the stack is as simple as writing the 8-word item to cvStack[cvStackPos..] followed by cvStackPos += 8, and to pop data from this stack we can just decrement cvStackPos -= 8 and not care about overwriting the previous item.

Using the new stack we can rewrite the merge code in the following copy-free way:

let totalChunks = chunkCounter;

while ((totalChunks & 1) === 0) {

cvStackPos -= 16; // pop 2 items

compress(

keyWords,

0,

cvStack, // -> blockWords

cvStackPos, // -> blockWordsOffset

cvStack, // -> out

cvStackPos, // -> outOffset

true,

0,

BLOCK_LEN,

flags | PARENT,

);

cvStackPos += 8; // push 1 item! (the out)

totalChunks >>= 1;

}This change gave us a 3x performance improvement and now we are around 3/4th of the speed of WebAssembly! Remember how we started from being ~2000x slower?

Step 6: Using Variables for blockWords

See this commit on GitHub: Use Local Variables to Access blockWords in Compress

Similar to step 4, our goal here is to do the same thing we did with state but this time with blockWords.

This means that we have to give up on the PERMUTATIONS table and do the permutations by actually swapping the variables because we cannot have dynamic access to variables.

First, we need to load the proper bytes into the variables:

let m_0 = blockWords[blockWordsOffset + 0] | 0;

// ...

let m_15 = blockWords[blockWordsOffset + 15] | 0;For the permutation, we can analyze the permutation pattern and optimize the swaps:

if (i != 6) {

const t0 = m_0;

const t1 = m_1;

m_0 = m_2;

m_2 = m_3;

m_3 = m_10;

m_10 = m_12;

m_12 = m_9;

m_9 = m_11;

m_11 = m_5;

m_5 = t0;

m_1 = m_6;

m_6 = m_4;

m_4 = m_7;

m_7 = m_13;

m_13 = m_14;

m_14 = m_15;

m_15 = m_8;

m_8 = t1;

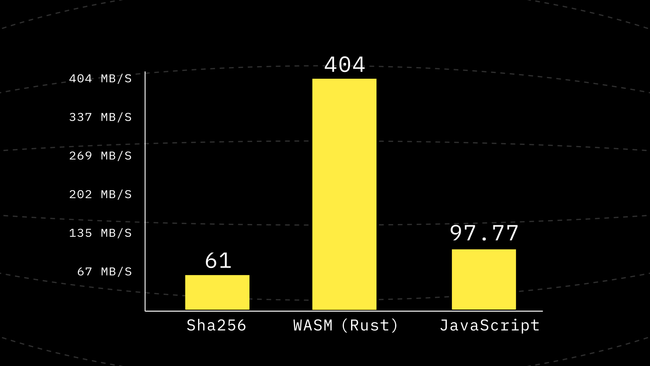

}Running this new version of the code shows another 1.5x improvement, reaching performance higher than WebAssembly for the first time so far. But just being a little faster is not a reason to stop.

Step 7: Reuse Internal Buffers

See this commit on GitHub: Reuse Global Uint8Array

This is a simple change. The idea is that once we create a Uint32Array either for blockWords or for cvStack, we should keep them around and reuse them as long as they are big enough:

// Pre-allocate and reuse when possible.

const blockWords = new Uint32Array(16) as W16;

let cvStack: Uint32Array | null = null;

function getCvStack(maxDepth: number) {

const depth = Math.max(maxDepth, 10);

const length = depth * 8;

if (cvStack == null || cvStack.length < length) {

cvStack = new Uint32Array(length);

}

return cvStack;

}

export function hash(input: Uint8Array): Uint8Array {

const flags = 0;

const keyWords = IV;

const out = new Uint32Array(8);

// The hasher state.

const maxCvDepth = Math.log2(1 + Math.ceil(input.length / 1024)) + 1;

const cvStack = getCvStack(maxCvDepth);

// ...

}The performance change here is not that much visible—it's only 1.023x which means going from 425MB/s to 435MB/s.

Step 8: Blake3 Is Little Endian Friendly

See this commit on GitHub: Optimize for Little Endian Systems

Blake3 is really Little Endian friendly and since most user-facing systems are indeed Little Endian, this is really good news and we can take advantage of it.

Right now even if we are running on a Little Endian machine, we still call readLittleEndianFull in order to read the input data into blockWords first before calling compress. However, if we're already on a Little Endian machine, that read is useless and we could allow compress to read directly from the input buffer without any intermediary temporary relocation.

const IsBigEndian = !new Uint8Array(new Uint32Array([1]).buffer)[0];

// ...

export function hash(input: Uint8Array): Uint8Array {

const inputWords = new Uint32Array(

input.buffer,

input.byteOffset,

input.byteLength >> 2,

);

// ...

for (let i = 0; i < 16; ++i, offset += 64) {

if (IsBigEndian) {

readLittleEndianWordsFull(input, offset, blockWords);

}

compress(

cvStack,

cvStackPos,

IsBigEndian ? blockWords : inputWords,

IsBigEndian ? 0 : offset / 4,

cvStack,

cvStackPos,

true,

chunkCounter,

BLOCK_LEN,

flags | (i === 0 ? CHUNK_START : i === 15 ? CHUNK_END : 0),

);

}

// ...

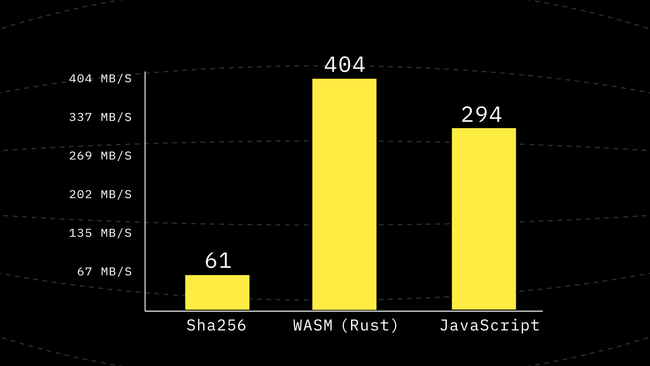

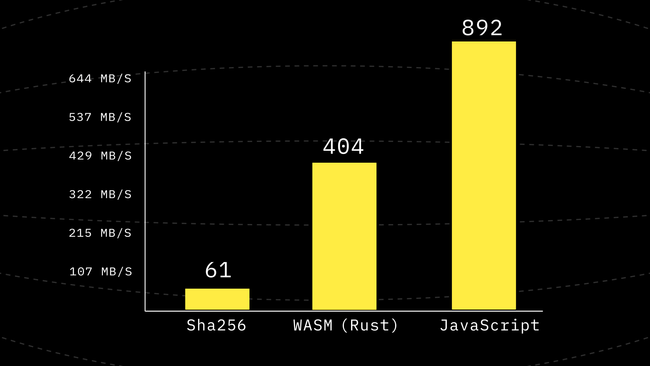

}With this change, we get yet again another 1.48x performance improvement! And now things look even better for JavaScript than WASM by some reasonable margin. Now we are 1.6 times faster than WebAssembly in pure JavaScript.

Giving WASM SIMD a Chance

Earlier in this blog I promised that we will not be shipping a WASM file. Of course in theory you can just encode the file in base64 and include it as text in JS. But who on earth would find that ok?

Since we already explored meta-programming and saw how small the generator code is, we can try to reuse the same ideas to generate the WASM file on load. This is of course something that is going to require us to understand the WASM binary format at a good enough level to write a WASM file by hand.

WASM Binary Format

A WASM module consists of a header and then a few (optional) sections. The header is only the magic bytes and the version of the module. These are hardcoded values. Then we have the following sections that we care about:

- SECTION 1: Types - Contains type definitions of the different functions in the module.

- SECTION 2: Imports - Where the WASM tells the host what needs to be imported (e.g., memory).

- SECTION 3: Functions - List of functions by their type alias.

- SECTION 7: Exports - Which functions are exported and their names.

- SECTION 10: Code - Function definitions including local variables and instructions.

const wasmCode = [

0x00, 0x61, 0x73, 0x6d, // magic

0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // version

// SECTION 1: Types

0x01, 0x04,

0x01,

// T0: func compress4x() -> ()

0x60, 0x00, 0x00,

// SECTION 2: Imports

0x02, 0x0b,

0x01,

0x02, 0x6a, 0x73, // mod="js"

0x03, 0x6d, 0x65, 0x6d, // nm="mem"

0x02, 0x00, 0x01, // mem {min=1, max=empty}

// SECTION 3: Functions

0x03, 0x02,

0x01,

0x00, // T0

// SECTION 7: Exports

0x07, 0x0e,

0x01,

// name="compress4x"

0x0a, 0x63, 0x6F, 0x6D, 0x70, 0x72, 0x65, 0x73, 0x73, 0x34, 0x78,

// export desc: funcidx

0x00, 0x00,

// SECTION 10: Code

0x0a, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x01,

// size:u32; to be filled later

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

// begin func:

0x01,

0x20, 0x7b, // 32xv128

// -- Instructions go here.

0x0b,

];What is SIMD?

SIMD stands for Single Instruction Multiple Data. It's basically a vectorized type. WASM supports v128 which means a vector consisting of 128-bits. Instructions can view this data in different ways—for example, i32x4 means 4 i32 values, or i8x16 for 16 bytes. Notice how the total size stays the same: 128=32×4=8×16.

Memory Layout

A simple call to our normal compress function works with 16 words of state if it reuses the state as the output. For compress4x, we need 4 times as much data, rearranged into vectors where each s[i] contains the values from all 4 inputs.

Some WebAssembly Instructions

WebAssembly is a stack-based virtual machine. Here are the key instructions we use:

| Name | Binary Format | Description |

|---|---|---|

local.get |

0x20, N |

Push $N to stack |

local.set |

0x21, N |

Pop into $N |

local.tee |

0x22, N |

Copy top to $N (no pop) |

i32.const |

0x41, ...LEB |

Push constant |

v128.load |

0xfd, 0, ALIGN, OFFSET |

Load v128 from address |

v128.store |

0xfd, 11, ALIGN, OFFSET |

Store v128 to address |

v128.or |

0xfd, 80 |

Bitwise OR two v128 |

v128.xor |

0xfd, 81 |

Bitwise XOR two v128 |

i32x4.shl |

0xfd, 171, 1 |

Left shift i32x4 by i32 |

i32x4.shr_u |

0xfd, 173, 1 |

Unsigned right shift i32x4 by i32 |

i32x4.add |

0xfd, 174, 1 |

Add two i32x4 |

Using only these 11 instructions we can implement the compress4x function.

Generating the Code

Since we placed blockWords in $0..$15, we can simply use the same permutation tables as variable indices. Anywhere we had state[i] we access $[16 + i]:

// Mix the columns.

g(16, 20, 24, 28);

g(17, 21, 25, 29);

g(18, 22, 26, 30);

g(19, 23, 27, 31);

// Mix the diagonals.

g(16, 21, 26, 31);

g(17, 22, 27, 28);

g(18, 23, 24, 29);

g(19, 20, 25, 30);Step 9: Simple use of compress4x

See this commit on GitHub: Use WASM SIMD

We take as many 4KB chunks of data as we can (except for the last block) and pass them to compress4x. Since WASM is always little-endian, we make sure the bytes are also little-endian before writing them to the WASM memory.

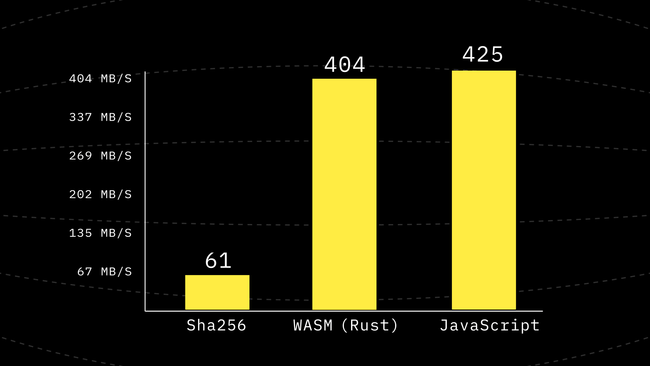

We can see a 1.39x improvement from the last benchmark. At this point, we're 2.21x faster than the WebAssembly implementation we started with. And the good news is our WASM never asks for more memory pages—it only ever needs 1 page regardless of the input size. Which in itself is a huge win for us.

Future Work

Blake3 is an awesome hash function—one that has unlimited potential for parallelization and optimizations. In this blog we focused on the performance of V8, so expect a detailed benchmark on different browsers and engines at some point.

Another path that was explored but did not make it to the blog is asm.js. All I have to say about asm.js is that V8 is already so good at static analysis that asm.js did not make much of a difference. However, it did improve the performance of the pure JS compress function on Firefox when I tested it a few months back.

And of course, an important task is packaging all of this in a nice and easy-to-use module. So stay tuned for the release! In the meantime, if you're using Deno, you know how to import a file from GitHub. So don't be shy and go ahead and star this blog's repo.